ARIEL SEIDMAN-WRIGHT

Margaret Bourke-White

Unless otherwise noted, all quotations from

Portrait of Myself by Margaret Bourke-White, and all images taken by her

(Margaret Bourke-White/ The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images)

by Ariel Seidman-Wright

“I stayed alone on the Embassy roof and began putting my camera to work. Incendiary bombs were falling, and flames began shooting up in scattered spots, giving me pinpoints of light on which I could focus on the ground glass of the view camera…I cannot tell what it was that made me know the bomb of the evening was on its way. It was not sound and it was not light, but a kind of contraction in the atmosphere which told me I must move quickly. It seemed minutes, but it must have been split seconds, in which I had time to pick up my camera, to climb through the Ambassador’s window, to lay the camera down carefully on the far side of the rug and lie down beside it myself. Then it came. All the windows of the house fell in, and the Ambassador’s office windows rained down on me. Fortunately, a heavy ventilator blown in from the windowsill missed me by a comfortable margin. I did not know until later that my fingertips were cut by glass splinters.”

When the Germans began air attacks on Moscow on July 22nd, 1941, Margaret Bourke-White found herself with the biggest scoop of her life: she was the only photographer representing any foreign publication in Russia, and lunged at the chance to capture the action. She photographed the bombing night after night from the roof of the American Embassy, setting up as many as four cameras at a time to capture the light streaking across the sky, with a fifth camera safely in the basement as back up. When she wasn’t hiding under the bed from Russian blackout wardens who made frequent checks for lawbreakers like her, she developed her photos in the enormous bathtub. After a night of intense bombing, Bourke-White left notes on the highest piles of glass, pleading with staff to avoid sweeping anything up until she could photograph the destruction in daylight. One of her other daytime photo subjects

was the elusive and stern Joseph Stalin. Her pictures, published in a lead story for Life Magazine, were the first images of the bombing of Moscow. This habit of running towards danger, eager to catch an exclusive story would become a hallmark of her career as “Maggie the Indestructible.”

Long before she was risking life and limb to photograph the light, spark, and explosions of war, Margaret Bourke-White was fascinated by the light and spark of a factory, which she visited as a young girl with her father:

“In a rush the blackness was broken by a sudden magic of flowing metal and flying sparks. I can hardly describe my joy. To me at that age, a foundry represented the beginning and end of all beauty. Later when I became a photographer, with that instinctive desire that photographs have to show their world to others, this memory was so vivid and so alive that it shaped the whole course of my career.”

Margaret Bourke-White was born June 14th, 1904 in The Bronx, New York City. Her father Joseph White was an inventor and engineer, and her mother, Minnie Bourke was a resourceful homemaker. Both encouraged a love of nature and science, and Margaret and her two siblings nurtured many creatures, including more than one pet snake.

Between 1922 and 1926, Margaret attended six colleges including Columbia, University of Michigan, Purdue, Western Reserve, and Rutgers. During these years, she explored a diverse range of study including herpetology, paleontology, dance, and one photography course. She met and married Everett Chapman in 1924, though their marriage lasted only two years. After this separation, she decided to finish her studies at Cornell, largely drawn to the campus because of Ithaca’s dramatic waterfalls and pristine nature. She used a secondhand ICA reflex camera— a gift from her mother— to photograph the university buildings and surrounding scenery. Perhaps, through this work, she felt a connection to her photo-enthusiast father, who had passed away in 1922.

In order to support herself, she sold her photos as holiday gifts, and once those sales dried up, Cornell’s Alumni Review purchased her images for their covers, encouraging her to pursue architectural photography. Upon graduating from Cornell in 1927 with a Bachelor of Arts, she travelled to Cleveland, finalized her divorce, and legally hyphenated her last name to Bourke-White.

In Cleveland, Bourke-White honed her technical skills, often under the mentorship of Alfred Hall Bemis, who owned a camera store, and Earl Leiter a “wizard of a photofinisher” who taught her about flash powder, coming to the rescue on her first job requiring artificial light—shooting a live bull inside a bank. She photographed architecture and landscapes to make a living, developing photos in her kitchen sink, but felt a magnetic pull to the industrial area of Cleveland and longed to go inside the mills to photograph. As a woman, she was barred from entry to the factories but she persisted, and was eventually allowed to photograph inside the Otis Steel Mills. Luckily, the head of the company went to Europe for five months, so she had ample time to figure out through copious trial and error how to capture images under such dark, nearly impossible circumstances. Half a year after she had started her experimentation, she presented the results to the head of Otis Steel Company who was impressed and purchased eight of her photos to be published in the book The Story of Steel.

“To me these industrial forms were all the more beautiful because they were never designed to be beautiful. They had a simplicity of line that came from their direct application to a purpose. Industry, I felt, had evolved an unconscious beauty— often a hidden beauty that was waiting to be discovered. And recorded! That was where I came in.”

Otis Steel Mills, Cleveland. Margaret Bourke-White, 1928

Margaret’s steel photographs caught the attention of Henry Luce, who, in 1929 invited her to New York to meet about the new Fortune Magazine. She was thrilled to learn that Luce and Parker Lloyd-Smith, the managing editor, were striving to create a magazine focusing on industry, where stories would be told with pictures and words as conscious partners. This was not typical of the time, when most publications focused on the written story and often picked up illustrations at random. Bourke-White shared their philosophy that pictures could be beautiful but must also tell facts, and accepted the job offer immediately. She wrote to her mother:“I feel as if the world has been opened up and I hold all the keys.”

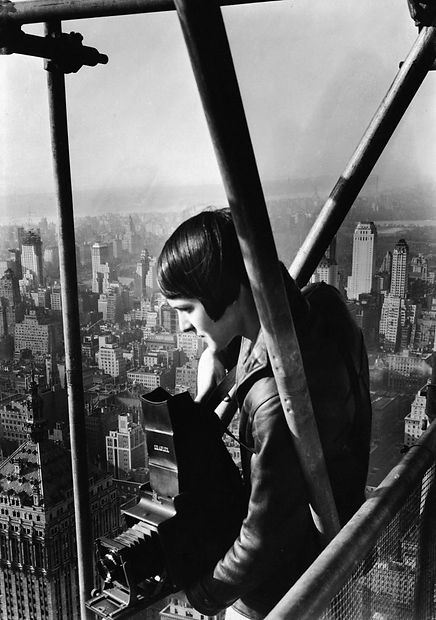

Her assignments for Fortune took her across America to photograph everything from shoemaking to glassblowing, orchid raising to hog slaughter. On October 24th, 1929, she was on overnight assignment photographing the interior of a bank, increasingly annoyed that bank staff were still at work, racing around and getting in the way of her long exposure photos. As she would soon find out, this was the fateful night of the stock market crash that ushered in The Great Depression. In spite of the new economic challenges, Fortune survived, and during the winter of 1929-30, Bourke-White worked in subfreezing temperatures photographing 800 feet above street level from the 61st floor of the Chrysler building. She was unfazed by the fact that the building would sway in the wind as she hung over the edge to capture a bird’s eye view. The challenges of this work were perhaps balanced out by the fact that during this time, she had a penthouse studio to work in complete with a tropical fish tank built into the wall, a large terrace for parties, and a small terrace for her turtles and two pet alligators. When she wasn’t working on assignment for Fortune, she did advertising photography in New York City, and noted that the gift of this type of work was practice in precision, even if it felt somewhat insane to navigate technical challenges like making three separate color plates just to photograph ice cream.

Chrysler Building Spire,

New York.

Margaret Bourke-White

1931

Left & Below:

Margaret Bourke-White working on the Chrysler

Oscar Graubner

The LIFE Images Collection via Getty

1930

Margaret took a break from the lucrative and (often logistically bizarre) world of advertising photography to travel to Germany on assignment for Fortune. Next, she set her sights on the Soviet, and was reassured that her portfolio, with award winning photos featuring “the drama of the machine” would be passport enough to impress Russian officials and gain entry. Even with such a strong portfolio, it took the persistence of showing up every day for 5 weeks to the Russian Embassy to finally receive a travel visa. This made Bourke-White the first foreign photographer allowed across the Russian border to see how the Soviet Five-Year Plan was unfolding. “Nothing attracts me like a closed door. I cannot let my camera rest until I have pried it open, and I wanted to be first.”

In 1936, Margaret signed on to accompany writer Erskine Caldwell to the Deep South to work on a piece about the lives shaped by the Dust Bowl drought. This would ultimately become the book You Have Seen Their Faces, and prove to be a turning point in many ways. Through their collaboration, Bourke-White and Caldwell fell in love and would eventually marry. Perhaps of more importance, this experience pushed Margaret to the resolution of only using photography to undertake assignments she respected that were both creative and constructive. Her social conscience had been fully awakened, and she stopped accepting commercial work, even though by this point she was being offered $1000/picture (equal to over $19,000 today) for some advertising contracts.

“I had never seen people caught helpless like this in total tragedy…I was deeply moved by the suffering I saw and touched particularly by the bewilderment of the farmers. I think this was the beginning of my awareness of people in a human, sympathetic sense as subjects for the camera and photographed against a wider canvas than I had perceived before…Here were faces engraved with the very paralysis of despair. These were faces I could not pass by.”

From You Have Seen Their Faces. Margaret Bourke-White, 1936

Later that year, Life Magazine came into existence, and Margaret Bourke-White’s photo of the Fort Peck Dam would be their first cover. Her work in the Columbia River Basin demonstrated her skill for using images to create a stirring portrait of the human experience within a larger, historical context, and this photo essay type of story came to be known as a “Bourke-White Story.” She was passionate about the mission of Life as a magazine: “it should help interpret human situations by showing the larger world into which people fitted. It should show our developing, exploding, contrary world and translate it into pictures.” It was no secret that her professional work came first, and Life was her first priority. She only agreed to marry Erskine once he signed a marriage contract that included a number of conditions, primarily that “there must be no attempts to snatch [her] away from photographic assignments.” They often travelled together and were married for five years, but parted ways when Caldwell wanted to move to Hollywood, buying her a house as enticement, but Margaret felt it was another set of “golden chains.”

“A women who lives a roving life must be able to stand alone. She must have emotional security, which is more important even than financial security. There is a richness in a life where you stand on your own feet, although it imposes a certain creed…You set your own ground rules, and if you follow them, there are great rewards.”

In 1942, Bourke-White was accredited to the U.S. Air Force, and both the Pentagon and Life would use her photos. The first uniform for a woman war correspondent was sewn, and she flew to England, where she photographed Winston Churchill and Haile Selassie. Despite the honour of being a pioneer, “invisible ink” often barred Bourke-White from missions which male photographers had no trouble receiving access to. There was a prevalent attitude that a woman’s presence on serious air missions would prove distracting for the pilots. So distracting, in fact, that when Margaret discovered a secret plan to invade North Africa, the Air Force insisted that she could only come if she take the “safer” journey on a boat rather than fly with the Air Force. She couldn’t tell her editors at Life that she was leaving for North Africa due to the secrecy of the mission, and along the way, her ship was torpedoed by a German submarine, which left Margaret and six thousand others stranded in the ocean with only a handful of functional lifeboats. As they floated in a lifeboat with a broken rudder, she took pictures of her fellow survivors, which would ultimately become her Life photo essay “Women in Lifeboats.”

“I look back on it as a dividing time in my life… We stood-all six thousand of us— at a crossroads, not just between personal death or life but between paralyzing self concern and that thought for others that transcends self. We were in a situation too vast for any one person to control, a catastrophe where people will show the qualities they have. For me it was an inspiring discovery that so many people—perhaps all normal healthy people— have a hidden well of courage, unknown sometimes even to themselves.”

Eventually they were rescued by another ship and brought to Algiers, where the Air Force finally agreed to let her accompany a bombing mission. Preparing to shoot photos from the bomber plane required numerous dress rehearsals to discern how to maneuver her camera while wearing thick electric gloves for the extreme cold and train in the oxygen apparatus; failing to plug in properly would give her only about 4 minutes of air. Bourke-White completed a successful mission on January 22nd, 1943, and became the first woman allowed to work in enemy combat zones. The intricacies of evasive action gave her every conceivable angle from which to take pictures, and although she reflected that “the impersonality of modern war has become stupendous, grotesque,” she became immersed in the unique vantage point to capture images.

Margaret continued her work with the Air Force in Italy, alternating between capturing photos hanging “out of an airborne birdcage with complete vision of earth and sky” and working through many nights in the trenches photographing heavy artillery. The Air Force heroes had been quite glamorized, but the Army was concerned that not much attention had been given to the people on the ground and their importance to the war effort, particularly the Engineers, Ordnance, Signal Corps and Medical Corps.

Bourke-White was often as close as thirty feet to a bomb shell and forced to climb out of debris, but was driven by a sense of purpose that if these people had to endure so much suffering, at least she was there to record it. She considered it a privilege to be alongside the heroic nurses, doctors, soldiers, and crew working under such harrowing conditions. Surgeons performed operations by hand held flashlights and nurses raced back and forth giving soldiers blood transfusions as quickly as ambulance drivers and corporals could donate blood. Unfortunately, this entire sequence of photos of these surgeons and nurses working under fire was lost somewhere between the dark room and the censor’s desk at the Pentagon. Life was able to salvage a story from the bits and pieces that remained from another roll with photos taken out of shell range, but Bourke-White was heartbroken, and flew to Washington to search for the photos herself, to no avail. Margaret’s negatives would meet a similar fate later in the war when she was photographing the Infantry on the “The Forgotten Front,” though this time they were stolen from a truck before even making it out of Italy. In this case she would return to re-take the photos before flying to Germany as the war raced towards its end in the crucial spring of 1945.

“We war correspondents were hard pressed to keep up with the march of events…No time to think about it or interpret it. Just rush to photograph it; write it; cable it. Record it now—think about it later. History will form the judgments.”

This dogged forward motion was certainly required in order to endure her next assignment: photographing the concentration camps at Buchenwald and Leipzig-Mochau as the Allies liberated Germany. Margaret was with General Patton’s Third Army when they reached Buchenwald, who were so enraged that they brought back two thousand German civilians to see with their own eyes what their leaders had done. Bourke-White wrote in her memoir that Buchenwald was “more than the mind could grasp,” with piles of naked, lifeless bodies, human skeletons in furnaces, and living skeletons who would die the next day because they had had to wait too long for deliverance.

The Liberation of Buchenwald. Margaret Bourke-White, 1945

“People often ask me how it is possible to photograph such atrocities. I have to work with a veil over my mind. In photographing the murder camps, the protective veil was so tightly drawn that I hardly knew what I had taken until I saw the prints of my own photographs. It was as though I was seeing these horrors for the first time. I believe many correspondents worked in the same self-imposed stupor. One has to, or it is impossible to stand it. Difficult as these things may be to report or to photograph, it is something we war correspondents must do. We are in a privileged and sometimes unhappy position. We see a great deal of the world. Our obligation is to pass it on to others.”

After V-E Day, Bourke-White travelled to Essen to do a story on the Ruhr, where she photographed and interviewed Herr Krupp of the prominent Krupp dynasty while he was under house arrest. He evaded her questioning about the atrocities of the camps and gave insolent answers to why he had done nothing. Several months later, she published her book Fatherland, Rest Quietly, and the US Treasury made use of it in the Nuremberg trials, forcing Herr Krupp to testify in front of a tribunal regarding the truthfulness of the statements he had made in their interview.

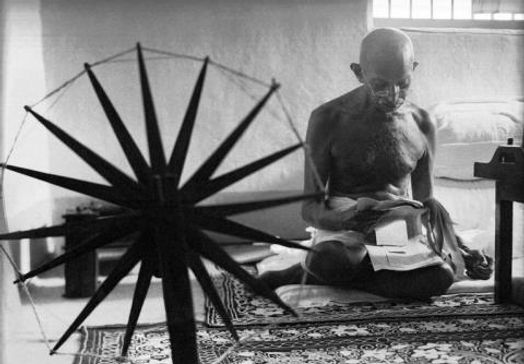

Margaret was eager to have a break from Europe and travelled to India in 1946, on the brink of the country’s independence. Part of her assignment was to photograph Gandhi, and his secretary insisted that she learn to spin on a wheel before being allowed to meet the Mahatma. After some initial protestations, she eventually relented and learned how to spin well enough that she could be brought into Gandhi’s presence, though she could not speak to him, as it was a Monday, his day of silence. Bourke-White later surmised that “the rule set up by Gandhi’s secretary was a good one: if you want to photograph a man spinning, give some thought to why he spins.”

Soon, Bourke-White had to leave the peace of Gandhi’s mud hut to travel to Calcutta. Violent rioting had broken out on the heels of Muhammad Ali Jinnah’s announcement of Direct Action Day, where he warned Congress “We will either have a divided India or a destroyed India.” Margaret did her job of recording the horror and brought the pictures out for Life, but found the task hard to bear. Life assigned her a photo essay on the caste system, and she travelled to South India to meet the families and children of the “untouchable” caste who labored in the leather tanneries of Madras, doing the hazardous work of pressing lime solution into leather with their bare feet. Even with new laws intended to undermine the caste system and protect children from dangerous jobs, Bourke-White saw how corruption made it difficult for these laws to be enforced. Still, she was inspired by the resilient spirit of the people she met, and the strides of a young country aiming to create a new democratic constitution.

Upon returning home to the United States, Margaret wanted to write a book based on her experiences in India, and knew she had to go back. As it so happened, Life commissioned her to do a story on the great exchange of populations and the new nation of Pakistan, and CBS hired her to do live broadcasts. She discovered that the violence had multiplied, and along with the tumult of religious terrorist attacks, people were suffering from the worst flood in forty years. Bourke-White photographed heartbreaking subjects in the streets, and also Jinnah himself, in what was likely his final portrait before his death. She also visited Gandhi a number of times during this visit, and was within arm’s length when he took his last bite of boiled beans before his final fast. On January 30th, 1948, she sat with him and discussed the philosophies of prayerful action, peace, and non violence. A few hours later, just a few blocks away, Gandhi was assassinated. Margaret had recorded some of India’s greatest moments and most tragic acts— she claimed that nothing in all her life affected her more deeply.

In 1950, Life sent Bourke-White to South Africa, where she witnessed apartheid first hand and saw parallels to the way Black people were treated in the United States. She descended deep into hazardous gold mines for hours, even though officials wanted her to stay in only “convenient” areas where it would be “easier to take photos.” She insisted that she needed to closely follow two specific miners and see their actual workplace, no matter the risk. She visited vineyards, shanty towns, farm jails and diamond mines and learned how the intense exploitation of Black South Africans by White South Africans was supported by structures of oppression that shaped every aspect of life.

Over the course of five months in South Africa, Margaret produced four photo essays for Life. Some contemporary scholars like John Edwin Mason note that these were “most American’s visual introduction to Apartheid,” but are critical that the political insight revealed in Bourke-White’s letters was absent from her photo essay. Mason argues that she and the editors of Life failed to create a multi-dimensional representation of the situation in South Africa, since they did not put enough focus on the Black activism of the time. In her memoir, Bourke-White wrote about the moral challenges she faced while working on these photo essays:

“For me the South African assignment was an exercise in diplomacy. I felt it called on all my powers. It underlined a dilemma in which I found myself with increasing frequency, both in and out of Africa. What are you going to do when you disapprove thoroughly of the state of affairs you are recording? What are the ethics of a photographer in a situation like this? However angry you are, you cannot jeopardize your official contacts by denouncing an outrage before you have photographed it.”

Johannesburg. Margaret Bourke-White, 1950

When Life sent her to Korea in 1952, the Korean War had been raging for two years, and numerous war correspondents had covered the action on the frontlines. Bourke-White had a different goal— she wanted to investigate the experience of the Korean people. When she arrived, she discovered a war within a war between Communist guerrillas and more neutral Koreans, where divided loyalties often tore families apart. She chose to focus her assignment on this “war of ideas which cut through every village and through the human heart itself.” At one point, the Communist guerrilla fighters put a price on her head, since they were not happy about an American woman taking photos in their midst. She would hike into the mountains with a mostly Korean crew to follow the threads of specific human stories, and when she needed to reach remote villages, was dropped off by helicopter.

Above: Churl-Jin and his mother are reunited. Margaret Bourke-White, 1952

Below: Margaret Bourke-White shares a meal with South Korean soldiers, 1952

Margaret was going back and forth between Korea and Japan in 1953 when she started to develop a dull ache in her left leg that sometimes travelled to her arm. Doctors had a difficult time diagnosing her initial symptoms of “whisper” paralysis, and it didn’t even occur to Bourke-White that this was the beginning of a battle with an incurable disease: “I had always been arrogantly proud of my health and durability. Strong men might fall by the wayside, but I was Maggie the Indestructible.” Once Margaret received the diagnosis of Parkinson’s, she had to follow a regiment of physical therapy. She scoffed at the suggestion of stirring cake batter to keep her wrists mobile, but did adopt a routine of crumpling newspaper and wringing out towels. In 1959, she underwent a new kind of brain surgery where she was awake while the doctors operated in order to test various functions. This first operation treated only her left side, so two years later, she returned to have the surgery to treat the right side of her body. During her post-op stay in the rehab facility, Alfred Eisenstaedt, a friend and colleague since the very first days of Life magazine, visited and began following her with his camera. They decided to document her experience with Parkinson’s as well as observe other patients, and their collaboration eventually became a photo essay for Life.

“I realized this was an assignment, the greatest in my life, and to accomplish it successfully I must be willing to travel anywhere and must try to learn everything. As long as I thought of it in the context of my work, it held no fears for me…in this experience of mine, there was one continuing marvel: the precision timing running through it all. The ailment which was draining al the good out of my life is one of the world’s oldest diseases…by great good fortune, I am born in the right century, in the right decade, and even in the right group of months to profit from the swift-running advance of modern medical science…by some special graciousness of fate I am deposited— as all good photographers like to be— in the right place at the right time.”

Margaret Bourke-White waged an 18 year battle with Parkinson’s and in 1971, at age 67, died in Stamford, CT. On assignment for Life, she had travelled all over the world and stood right in the middle of both the heroism and atrocities of war. In nearly every photo essay, she was able to zoom in on the unique, personal perspective and zoom out to see the wider scope, where much of human life is abstracted. An unparalleled journalist, she constantly risked her life across four continents to photograph wars, industry, and political and social revolutions. Margaret Bourke-White was the epitome of trailblazer, and her ability to distill complex social commentary into a single image would forever change the field of photojournalism.

Left: photo by Alfred Eisenstaedt, The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images, 1959

Right: photo by M. McKeown, Getty Images, 1964

Bourke-White's photographs can be found in the Brooklyn Museum, the Cleveland Museum of Art, the New Mexico Museum of Art and the Museum of Modern Art in New York as well as in the collection of the Library of Congress.

Many of her manuscripts, memorabilia, photographs, and negatives are house in Special Collections at Syracuse University.

She wrote seven books including Eyes on Russia, Halfway to Freedom, Purple Heart Valley, and her memoir Portrait of Myself, which was published in 1963.

CHECK OUT...

The online archive of the Margaret Bourke-White collection at MoMa

(click on logo)

This is a book by Linda Skeers for youth, but honestly, I really enjoyed it, and the illustrations by Livi Gosling are great.

From the length of this profile, you can probably guess that I found Bourke-White's 391 page memoir FASCINATING. She's a strong writer, and there's a whole lot of her life (and photos) I didn't even mention.

click the images to find the books on amazon, BUT if you can, support your local, independent bookstores!